Prior to the enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act (1965), foreign nationals from a select few European countries were the only ones who really had a realistic chance at immigrating to the United States. However, with the passage of this new law, these types of discriminatory immigration practices were removed, and it drastically improved immigration opportunities for everyone else in the world. As National Public Radio correspondent and author Tom Gjelten reveals in A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story (2015), this new act made it possible for nine Bolivian immigrants in particular to come to the US and have a chance at success.[i]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Aida, Marilu, and Rhina lived with their mother, Eduviges Veizaga, in La Paz, Bolivia. In 1980, a friend convinced Aida and Marilu to go with her to Washington, DC, so that they could go to college in the area. Neither Marilu nor Aida had ever been to the US before, which was fairly common for the majority of Bolivians at the time. According to Gjelten, “[o]nly about sixty Bolivians visited the United States on an average day that year, and almost all of them were businessmen, government officials, or wealthy Bolivian tourists traveling for pleasure. Just three countries in South America—Guyana, Paraguay, and Uruguay—sent fewer visitors to the United States.”[ii] Unfortunately, Marilu and Aida’s first trip to the US was a bust; they did not speak English very well and did not know their way around the area. Even worse, their travel liaison failed to register them for college and swindled them out of their money. Consequently, Marilu and Aida took on jobs as nannies in lieu of attending college. Both were miserable and eventually returned to Bolivia; however, Marilu and Aida would come back to the US a couple of years later.[iii]

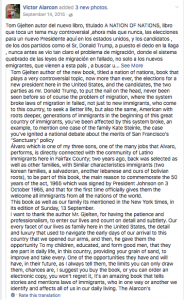

(Image Courtesy of Ancestry.com)

Marilu’s second trip to the US was much more successful than her first. She was better prepared and took English classes upon her arrival. Through family and friends, she found her future husband, Raúl Plata. Raúl was a fellow Bolivian immigrant and dentist in northern Virginia who had already become a naturalized US citizen. On her marriage to Raúl on December 22, 1984, Marilu was granted legal residency.[iv] According to their marriage license, Raúl was born in Bolivia, and his parents were Placido Plata and Genoveva DePlata. He was 39 years old at the time, white, had gone to college and probably dental school, and lived in Vienna, Virginia. Meanwhile, Marilu was listed as having been born in Boliva to Luis Luna and Eduviges Veizaga. She was 21 years old at the time, white, had finished high school, and lived in Falls Church, Virginia. They had a religious ceremony in Fairfax County that was officiated by Pastor John Goodwin. It was both Marilu and Raúl’s first marriage.

By the time of Marilu’s marriage to Raúl, her oldest sister, Rhina, had married Victor Alarcón and had two kids, Victor Jr. and Alvaro.[v] Victor came to the US first on a tourist visa and lived with Marilu in Fairfax County until he could afford his own apartment. Victor’s transition to the US was not easy; he worked several jobs, had been the victim of a shooting, and his home was burglarized. Yet, notwithstanding these hardships, his drive and determination led to his perseverance and success. He ultimately saved enough money for Rhina to join him in the US and she worked just as hard as him. However, despite his hard work ethic and optimistic attitude, like Marilu, Victor realized that English literacy was required if he was going to truly succeed. Therefore, Victor utilized the public library and translated words via language dictionaries in order to teach himself how to repair cars and household electronics.[vi] Meanwhile, the Alarcóns two boys and daughter eventually joined the Platas and Alarcóns in the US.[vii]

It has been over thirty years since these nine Bolivian immigrants came to the US, and it is apparent through Facebook and other online sources that they are the personification of the American dream.

Raúl and Marilu

(Photographs Courtesy of Facebook)

Raúl’s business website states that he attended dental school at Virginia Commonwealth University and earned a doctor of dental surgery. His dental clinic is located in Fairfax, Virginia.[viii] Records indicate that his business was previously located in Falls Church.[ix] As for his home residence, he lived in the City of Fairfax.[x]

(Photographs Courtesy of Zocdoc, Inc.)

Raúl’s Facebook profile shows that he has embraced some “American” cultural traits. For example, he is a fan of the National Football League and cheers for the Dallas Cowboys. Though he listens to bands that are popular in many other countries, such as the Beatles, the Who, and the Rolling Stones, he also likes uniquely American bands, like Lynyrd Skynyrd, which is in the southern rock genre.[xi] As for Marilu, her Facebook privacy settings restrict those who are not her friends from viewing anything other than her profile picture.[xii]

Victor and Rhina

(Photographs Courtesy of Facebook)

On their Facebook accounts, Victor and Rhina have posted numerous pictures of themselves as a couple throughout the years, so it is likely that they are still married.[xiii] Many of their pictures have La Paz, Bolivia, listed as the location, indicating that they have visited their home country.

(Photograph Courtesy of Facebook)

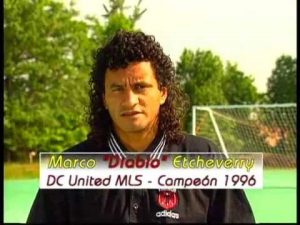

Like Raúl, Victor has adapted to life in Virginia; however, between the two, Victor was the only one to choose the correct NFL team to support (e.g. Washington Redskins)! Victor also listens to American bands, like the Eagles, and even country music; most surprisingly, he is a fan of the heavy metal band, Hatebreed. Additionally, on Victor’s page, he posted the following about A Nation of Nations (translated from Spanish to English using Facebook translation):[xiv]

(Images Courtesy of Facebook)

Gloria

(Photograph Courtesy of Facebook)

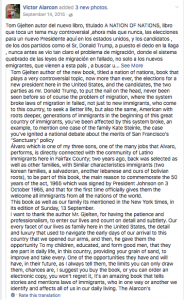

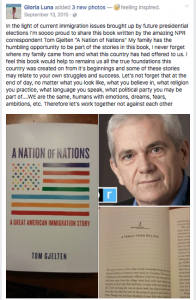

According to Gloria’s Facebook page, she is a small business owner at Luna’s Cakes, account liaison at Heartland Home Health Hospice and IV Care, and a Zumba fitness instructor. Additionally, on September 13, 2015, Gloria posted the following Facebook post:[xv]

(Image Courtesy of Facebook)

(Image Courtesy of Facebook)

Aida

(Photographs Courtesy of Facebook)

Aida also has a Facebook account and it appears that she permanently resides in Bolivia. However, there are many pictures that show her with Rhina and Raúl, so it is clear that they are still a close-knit family.[xvi]

(Photographs Courtesy of Facebook)

[i] Tom Gjelten, A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015). According to the National Public Radio’s (NPR) website, Gjelten has been with NPR since 1982 and he is the recipient of two Overseas Press Club Awards, a George Polk Award, and a Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award. For more, see National Public Radio, “Tom Gjelten,”accessed November 16, 2016, http://www.npr.org/people/2100536/tom-gjelten.

[ii] Gjelten, 23.

[iii] Gjelten, 23-24.

[iv] Gjelten, 24; Virginia, Marriage Records, 1936-2014, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[v] Gjelten, 22, 25. Victor was born in Argentina but grew up in Bolivia.

[vi] Gjelten, 26, 50-51, 218-20, 233-34.

[vii] Gjelten, 27.

[viii] Zocdoc, “Dr. Raúl E. Plata, DDS,” accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.zocdoc.com/dentist/Raúl-e-plata-dds-164765.

[ix] U.S. Phone and Address Directories, 1993-2002, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[x] U.S. Phone and Address Directories, 1993-2002, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xi] Raúl’s Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100008295788890.

[xii] Marilu’s Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/marilu.plata.35/friends?source_ref=pb_friends_tl.

[xiii] Victor’s Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/victor.alarcon.399?fref=ts; Rhina Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/rhinaalarcon.

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Gloria’s Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/gloria.luna.944?pnref=friends.search.

[xvi] Aida’s Facebook page, accessed November 10, 2016, https://www.facebook.com/aida.lunaveizaga/friends?source_ref=pb_friends_tl.

Photo Courtesy of the World Fact book-Central Intelligence Agency

Photo Courtesy of the World Fact book-Central Intelligence Agency

![[Figure 1: Doro Wot – courtesy of https://ethiopianfood.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/doro2a.jpg]](http://immigrantalexandria.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Doro-Wot-300x260.jpg)

![[Figure 2 – Map of Aida Abdul-Wali’s Life – Map Created by Helen Salita Using Google Maps]](http://immigrantalexandria.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Map-of-Aidas-Life-300x83.png)

![[Figure 1: Zilzil Tibbs – image courtesy of - https://ethiopianfood.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/teretibssiga.jpg]](http://immigrantalexandria.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Zilzil-Tibbs-300x215.png)

![[Figure 4: Courtesy of Café Caboose Online Menu - http://caboose-cafe.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Caboose-Dinner-Menu.finalprint.pdf]](http://immigrantalexandria.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/English-to-Amharic-Dictionary-300x88.png)