English learners in the United States public school system are invisible, unwelcome, and often mistreated. As the nation becomes more polarized and immigrants are a popular political point of discussion, educators may wonder if their English Language Learner (ELL) students will get the appropriate attention and materials they need to succeed. In Alexandria, however, programs have been established to protect, promote, and even advocate the cultures of their immigrant communities. As of the last U.S. Census in 2010, Alexandria’s population consisted of 16.1% Latinos.[1] This is a slight increase from the 2000 U.S. Census, with a 14.7% Latino population in Alexandria.[2] Legislation was put into effect to not only protect an ELL student’s mother tongue but to promote the maintenance of their culture. The Bilingual Education Act of 1968 states that students were to “be taught in their native languages while they learned English.”[3] The reality, however, is that ELL programs, usually called English as a Second Language (ESL) or English for Speakers of Other Languages (ESOL), fail to assist these students in any meaningful way. In the 1990s a Bolivian immigrant, Heidi Flores at T.C. Williams High School in Alexandria, specifically addressed a common sentiment of ELL students that resonates to this day: isolation.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, EDFacts file 141, Data Group 678, extracted November 3, 2015, accessed November 11, 2016.

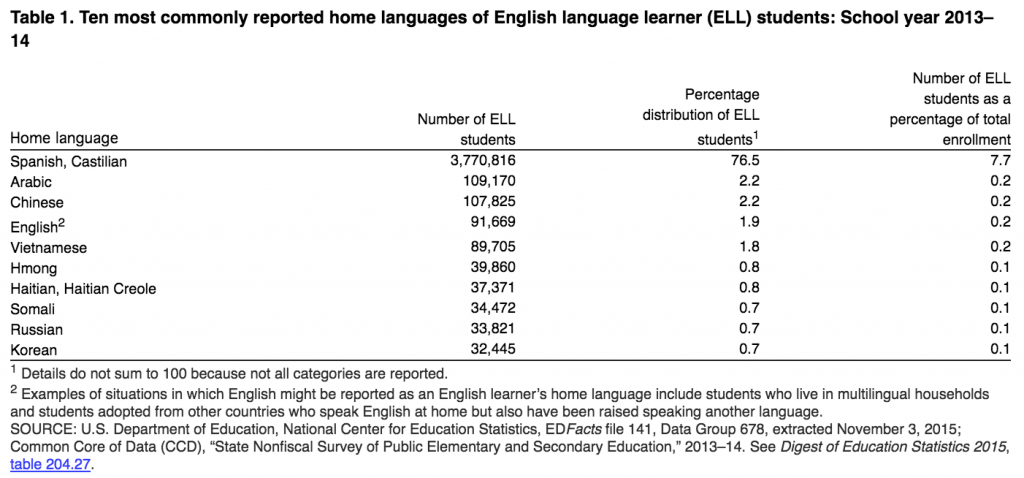

With a growing immigrant population, Spanish is not the only language ELL programs are servicing. However, Spanish-speaking students are the largest group of ELL students in the U.S. at 76.5% in the 2013-2014 school year with 3,770,816 students nationally.[4] In fact, there are more Spanish speakers in the United States than Spain.[5] Currently, Alexandria City Public Schools have a 36% Latino population.[6] In April 2015, T.C. Williams had over one thousand Latino students enrolled at their high school, making up 41% of the school’s demographic, a higher average than the city generally.[7] Yet, ELL students still feel unwelcome, stating that despite the ELL program at T.C. Williams being effective, they felt insignificant and unaccepted in the large school.[8] Most Bolivian immigrants are economic immigrants and many non-Western European immigrants that come to the United States experience downward mobility.[9] The result is that the ELL students in the U.S. have parents who work long hours or multiple jobs to make ends.[10] Moreover, many send remittances back to family in Bolivia, which forced them to live in low-income and often high-crime neighborhoods.[11] This absence of their parents can lead to gang involvement.[12]While certain gangs are generally known to associate with specific nationalities, such as MS-13 consisting primarily of Salvadoran immigrants, they actually are inclusive of other Latinos.[13] Flores explained how unwelcome the Latino students felt at T.C. Williams in the 1990s, stating that bullying ranged from attacking people for their accents to name-calling.[14] Joining a gang was a means of having family and community that some lacked at home and at school. While some find positive organizations, like Junior ROTC, others do not communicate with their teachers or school counselors that they lack appropriate clothes, access to food, and are being bullied.[15] This could partially be due to the fact that they may not be receiving what they need to learn English, and some lack the ability to read and write in Spanish as well.[16]

“ACPS Monthly Enrollment Data: April 2016,” Alexandria City Public Schools, April 2016, accessed November 19, 2016, http://www.acps.k12.va.us/enrollment-monthly-201604.pdf.

While certain gangs are generally known to associate with specific nationalities, such as MS-13 consisting of Salvadoran immigrants, they actually are inclusive of other Latinos.[13] Flores explained how unwelcome the Latino students felt at T.C. Williams in the 1990s, stating that bullying ranged from attacking people for their accents to name-calling.[14] Joining a gang was a means of having family and community that some lacked at home and at school. While some find positive organizations, like Junior ROTC, others do not communicate with their teachers or school counselors that they lack appropriate clothes, access to food, and are being bullied.[15] This could partially be due to the fact that they may not be receiving what they need to learn English, and some lack the ability to read and write in Spanish as well.[16]

Hope J. Gibbs, “T.C. Williams High School JROTC,” digital image, Alexandria News, May 15, 2008, accessed November 20, 2016, http://alexandrianews.org/2008/other-news/second-span-of-woodrow-wilson-bridge-dedicated/1166/.

Studies have shown that language acquisition can take five to seven years, but this can only occur with effective ELL instruction.[17] Bolivian immigrants, like most children of immigrants from non-English speaking countries, are raised in homes where English is not spoken, leaving both content and language learning to their teachers.[18] Afterward, many of the students teach their parents English or act as a translator because Spanish-speaking immigrants largely maintained their native tongue, particularly in comparison to other groups of immigrants.[19] The Bilingual Education Act was the first step at acknowledging a need to teach ELL students in both English and in Spanish.Northern Virginia is unique, however. With their growing Latino population, they chose to maintain its diversity with programs outside of schools as well. One such program is Edu-Futuro. The slogan for Edu-Futuro reads “Educación para nuestro futuro,” meaning education for our future and their motto reads “Empowering Students. Engaging Parents. Transforming Communities.”[20] This program aims to help Bolivian immigrants learn skills, culture, and advocate for other themselves, their families, and the growing community. They were “recognized as a Bright Spot in Hispanic Education by the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics on September 15, 2015” because of their work to better educate the Latino community.[21] Ultimately, this program and ones like it may be able to curb the isolation ELL students feel and show teachers how to reach out to these students. Had Flores and the students she spoke for in the 1990s had access to a program like this they could have found the community they desired to escape the isolation of their school.

Jane Hill and Kathleen Flynn, “The Stages of Second Language Acquisition,” in Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2006), 15.

Northern Virginia is unique, however. With their growing Latino population, they chose to maintain its diversity with programs outside of schools as well. One such program is Edu-Futuro. The slogan for Edu-Futuro reads “Educación para nuestro futuro,” meaning education for our future and their motto reads “Empowering Students. Engaging Parents. Transforming Communities.”[20] This program aims to help Bolivian immigrants learn skills, culture, and advocate for other themselves, their families, and the growing community. They were “recognized as a Bright Spot in Hispanic Education by the White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for Hispanics on September 15, 2015” because of their work to better educate the Latino community.[21] Ultimately, this program and ones like it may be able to curb the isolation ELL students feel and show teachers how to reach out to these students. Had Flores and the students she spoke for in the 1990s had access to a program like this they could have found the community they desired to escape the isolation of their school.

Endnotes

- 2010 U.S. Federal Census: Community Facts; Hispanic or Latino, Alexandria, Virginia, American Fact Finder, digital image, accessed November 8, 2016, http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- 2000 U.S. Federal Census: Community Facts; Hispanic or Latino, Alexandria, Virginia, American Fact Finder, digital image, accessed November 8, 2016, http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml.

- Sara Davis. Powell, “Ethical and Legal Issues in U.S. Schools,” in Your Introduction to Education: Explorations in Teaching, 3rd ed. (Boston: Pearson, 2012), 286.

- “English Language Learners in Public Schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, May 2016, accessed November 08, 2016, http://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp.

- Chris Perez, “Us Has More Spanish Speakers Than Spain,” New York Post, June 29, 2015, accessed November 10, 2016, http://nypost.com/2015/06/29/us-has-more-spanish-speakers-than-spain/.

- “Fast Facts: Student Demographics,” Alexandria City Public Schools, September 30, 2015, accessed November 19, 2016, http://www.acps.k12.va.us/fastfact.php.

- “ACPS Monthly Enrollment Data: April 2016,” Alexandria City Public Schools, April 2016, accessed November 19, 2016, http://www.acps.k12.va.us/enrollment-monthly-201604.pdf.

- Pamela Constable, “A New Accent On Education: Rise of Immigrants Means Schools Must Navigate a Sea of Diversity,” The Washington Post, April 2, 1995.

- Tom Gjelten, A Nation of Nations: A Great American Immigration Story(New York: Simon & Schuster, 2015), 22-25.

- Gjelten, A Nation of Nations, 51-52.

- Ibid.

- Gjelten, A Nation of Nations, 298-299.

- Patrick Welsh, “Lure of the Latino Gang: When Immigrant Students Find Poverty, Isolation and a Life of Violence,” The Washington Post, March 26, 1995.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Jane Hill and Kathleen Flynn, “The Stages of Second Language Acquisition,” in Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners (Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, 2006), 15.

- Hill and Flynn, “The Stages of Second Language Acquisition,” in Classroom Instruction That Works with English Language Learners, xii-xiii.

- Gjelten, A Nation of Nations, 329.

- “Bright Spot in Hispanic Education,” Edu-Futuro, accessed November 10, 2016, http://www.edu-futuro.org/new-page-1/.

- Ibid.