Mass Ethiopian immigration to the United States is a rather new phenomenon. With the US enactment of the Immigration and Nationality Act (1965), it was not uncommon for an Ethiopian to travel to the US to pursue higher education. However, from 1974 to 1991, the Ethiopian Civil War prompted several key changes in American immigration law, including the Refugee Act (1980), Immigration Reform and Control Act (1986), and Immigration Act (1990). These new laws were responsible for allowing hundreds of thousands of Ethiopian refugees to flee the war zone and come to the US in the late twentieth-century, and many settled permanently in the Washington, DC metropolitan area.

(Image Courtesy of Google Maps)

(Article Courtesy of the Washington Post)

Ethiopian refugees quickly established a distinct community within the region, and their large footprint is apparent in Bill Broadway’s Washington Post article from May 2, 1998, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home: Orthodox Christian Community Keeps Tradition Alive in D.C. Area.”[i]

The article begins by describing a church service led by Reverend Abba Melaku Getaneh at Debre Mehret St. Michael’s Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church in Northeast Washington, DC. According to St. Michael’s website, “[t]he Debre Mehret St. Michael’s Church was founded on May 30, 1993. Initialy [sic], the Church was established in a small room by about 30 parishioners on the initiative of Komos Abba Melaku Getaneh (Abune Fanuel) in the Woodner Building located on 16th Street in Washington, D.C.”[ii] The article explains that there were four other Ethiopian Churches within the DC area at the time: Medhane Alem in Capitol Heights, Maryland; Debre Selam Kidest Mariam (also known as St. Mary’s); Debre Haile Kedus Gebriel (also known as St. Gabriel’s) in Washington, DC; and Kidane Mihret in Alexandria, Virginia.

(Created by Dino Reschke Using GoogleMaps)

Much can be learned about late twentieth-century Ethiopian immigration to the United States from just this one Washington Post article. First, Broadway describes St. Michael’s church service being held “in a converted electrical warehouse ….”[iii]

Outside of St. Michael’s (Image Courtesy of Google Maps)

According to Elizabeth Chacko, who is a geographer and one of the most prominent Ethiopian immigration researchers, the conversion and use of warehouse for church service is a prime example of heterolocalism and ethnic place-making.[iv] Like other late-twentieth century immigrants, Ethiopians resettled in a very densely populated area, so space for new construction and funding for a new establishment was not available. Therefore, Ethiopians took what they could get and re-purposed a warehouse into St. Michael’s Church with the idea that it would be a temporary facility until assets became available. As a result of converting an old warehouse into a church, Ethiopians had an ethnic institution that they could use to freely practice their religion and language, and it also created a place to network with other immigrants like them.

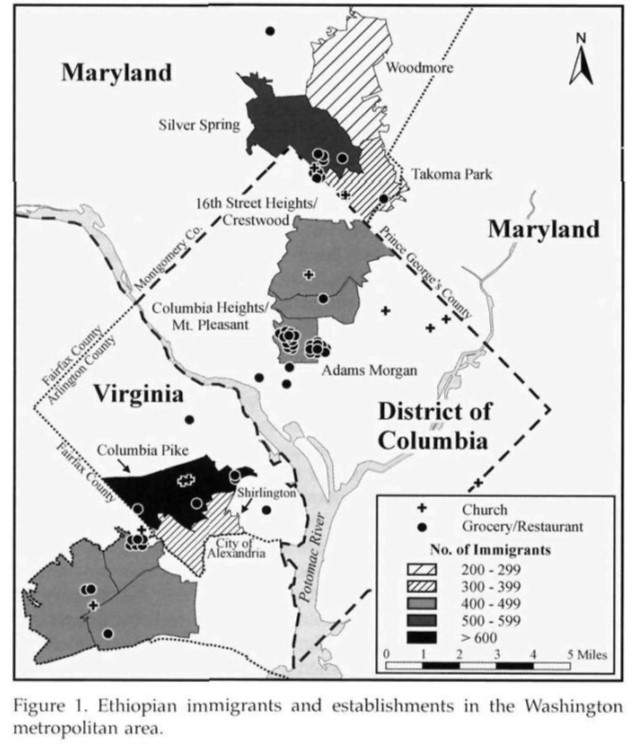

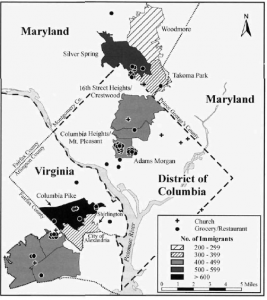

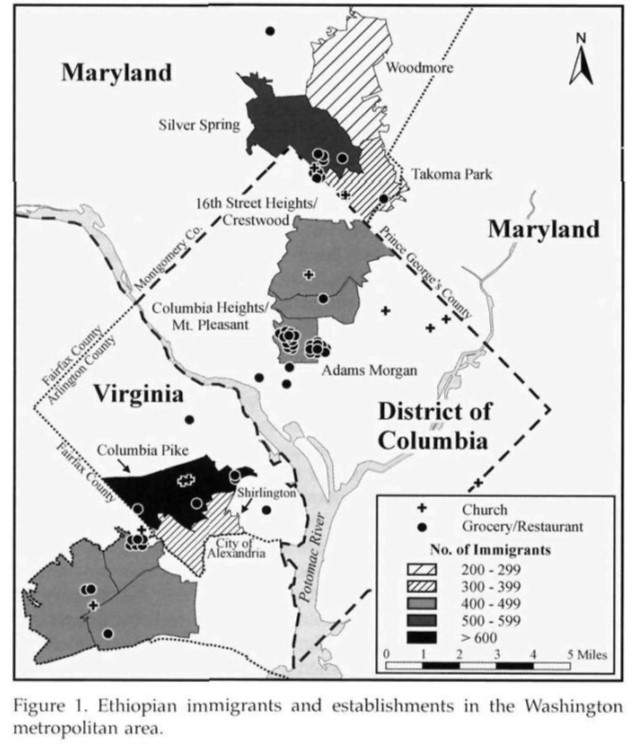

It is evident that due to the Washington, DC metropolitan area’s dense population at the time of their arrival, Ethiopian immigrants could not all live in one ethnic neighborhood like the Italians, Irish, or Chinese did in the early twentieth-century US metropolitan cities. Ethiopian refugees were forced to find homes wherever there were vacancies in the area.

(Image Courtesy of Elizabeth Chacko)

As demonstrated in the image to the right, this resulted in immigrants becoming highly scattered throughout the DC region, which is a classic example of residential dispersion.[v] This data also coincides with Elizabeth Chacko’s later survey of Ethiopian establishments in this region, which is provided on the right.

Two examples of Ethiopian culture are also presented in this article. Broadway states that “[m]ost of the women and girls, including babies wore a yabesha lebse, an Ethiopian dress and shawl made of a gauzy white cotton fabric with colorful hems.”[vi] Broadway also explains through an observation that while the people were singing and dancing, they were “frequently bursting out with a trilled ‘Yi-yi-yi.”’[vii] While these may seem like trivial points, these two examples of Ethiopians freely practicing their traditions while living in the US, maintaining connections to their heritage through the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.

Though it has been nearly twenty years since the publishing of Broadway’s article, Ethiopian immigrants and their children have continued to make the Washington, DC metropolitan area their home. With modern-day technology and the limited number of available public records, it is possible to learn more about the immigrants who are mentioned in this article, and to also visualize the distance that they had to travel in order to attend service at St. Michael’s.[ix]

(Created by Dino Reschke Using Google Maps)

Bizuayehu Ayalew was described as 27 years old and a “choir member” at St. Michael’s.[x] In 1993, Ayalew lived at 1355 Peadbody Street NW, Washington, DC.[xi] Then, in 1994 and 1995, Ayalew’s address was 8715 1st Avenue, Silver Spring, Maryland.[xii] Assuming that Ayalew did not move at the time that the newspaper article was written, Ayalew would have lived approximately 7.5 miles from the church via automobile or 40 minutes by walking and taking Metrorail.[xiii]

Dagne Gizaw was the “secretary of the board at St. Mary’s.”[xiv] Gizaw lived at 8008 Eastern Drive in Silver Spring, Maryland from 1994 through 2002.[xv] At the time of Broadway’s article, Gizaw lived approximately 6.5 miles from the church via automobile or 40 minutes by walking and taking Metrorail.[xvi] Additionally, the U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007 listed Gizaw as having a spouse, Zewiditu Nekenek, and a child, Abesha D. Gizaw.[xvii] An article featured in the Washington Post in 2006 included a statement from Gizaw, which identified him as now being a deacon.[xviii]

Fikre A. Gelaye was an “assistant pastor at St. Michael’s and secretary of a cooperative association for Washington area Ethiopian Orthodox churches.”[xix] Gelaye lived at 3010 Earl Place NE in Washington, DC in 1993 and again in 2000-2002.[xx] This address is very close to St. Michael’s Church, so being that Gelaye was an assistant pastor, it is likely that this property may have belonged to the church (such as a rectory). Additionally, it is plausible that Gelaye served in another church from 1994 to 1999 and came back to St. Michael’s in 2000, which would explain the gap in years reported for this address.[xxi]

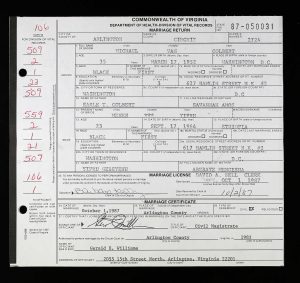

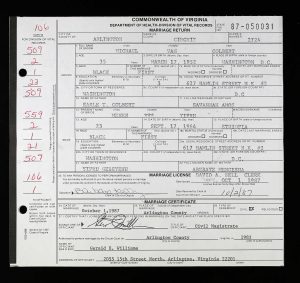

Menen Yifru’s Marriage License (Document Courtesy of Ancestry.com)

Menen Yifru was described as being 32 years old, a refugee, and “a Marriott employee who left Ethiopia 12 years ago and has attended St. Michael’s since its inception.”[xxii] Yirfu was born on September 17, 1964, and lived at 5510 N. Morgan Street Apt 203 in Alexandria, Virginia in 1991, and in an apartment at 621 Hamlin Street NE, Washington, DC in 1996. Assuming that Yifru did not move at the time that the newspaper article was written, she would have lived approximately 2.5 miles or roughly 10 minutes away from the church via automobile (Metrorail is unavailable from this address).[xxiii] Additionally, records indicate that Yifru married at least twice while living in the United States. Yifru’s marriage license from October 1, 1987, reflects that she first married Michael Van Colbert while living on 617 Hamlin Street NE #2 in Washington, DC. The marriage license lists that it was her first marriage, that she was born in Ethiopia, that she had one year of college education as opposed to her husband who had three years, and that her parents were Yifru Gebeyehu and Abebaye Mengesha.[xxiv] Though there is not a divorce record available online from her marriage with Colbert, records indicate that she later remarried Teawodros Gebeyehu on November 5, 1994, and subsequently divorced him on August 25, 2000.[xvv]

[i] Bill Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home: Orthodox Christian Community Keeps Tradition Alive in D.C. Area,” Washington Post, May 2, 1998, D8.

[ii] Debre Mihret Kidus Michael Church, “About,” accessed October 27, 2016, http://stmichael.welela.com/?q=node/30.

[iii] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8.

[iv] Elizabeth Chacko, “Ethiopian Ethos and the Making of Ethnic Places in the Washington Metropolitan Area,” Journal of Cultural Geography 20, no. 2 (Spring-Summer 2003): 24, 28.

[v] Ibid., 11-12.

[vi] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8.

[vii] Ibid.

[ix] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8. Three other members of the church were identified in a picture in this article; however, there are not any public records available online for these individuals (Frehwoi Lema and her child, Elshadye, and Deacon Netsere Taye).

[x] Ibid.

[xi] U.S. Public Records Index, 1950-1993, Volume 2, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xii] U.S. Phone and Address Directories, 1993-2002, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xiii] Google, “Google Maps,” accessed October 27, 2016, https://www.google.com/maps. While 7.5 miles may not seem like a long way to travel via automobile, the Washington, DC metropolitan area is known for its high amounts of congestion. It could take over an hour to travel a few miles during rush-hour traffic.

[xiv] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8.

[xv] U.S. Phone and Address Directories, 1993-2002, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xvi] Google, “Google Maps,” accessed October 27, 2016, https://www.google.com/maps.

[xvii] U.S., Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xviii] Debbi Wilgoren, “Ethiopians in D.C. Region Mourn Archbishop’s Death,” Washington Post, January 13, 2006.

[xix] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8.

[xx] U.S. Phone and Address Directories, 1993-2002, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com; U.S. Public Records Index, 1950-1993, Volume 2, accessed October 26, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com. There are not any available public records online that list Gelaye’s residence between 1994 and 1999.

[xxi] Google, “Google Maps,” accessed October 27, 2016, https://www.google.com/maps.

[xxii] Broadway, “For Ethiopians, Church a Home Far from Home,” D8.

[xxiii] Google, “Google Maps,” accessed October 27, 2016, https://www.google.com/maps.

[xxiv] Virginia, Marriage Records, 1936-2014, accessed October 25, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.

[xxv] Virginia, Marriage Records, 1936-2014, accessed October 25, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com; Virginia, Divorce Records, 1918-2014, accessed October 25, 2016, http://www.ancestry.com.