Airplane View of Alexandria, VA, ca. 1919 Creator(s): Harris & Ewing, photographers.

Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print

Introduction

The purpose of this project is to develop an understanding of the racial atmosphere surrounding Italian immigrants who lived and worked in and around Alexandria, Virginia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We have used a variety of primary sources, including the U.S. Census, newspaper articles, World War I Draft Cards, and city directories to support our arguments. Our secondary sources include books, articles, and dissertations about Italian immigration to the United States. Job opportunities for unskilled laborers were the primary reason for Italian immigration to Alexandria, although some skilled laborers such as shoemakers and small business owners were found residing in the area as well. Racial tensions arose between Italians and the native-born population due to the nature of the Jim Crow South and nativism, Close labor relations and competition with African Americans also produced local strife.

Thesis

Between 1880 and 1920, young Italian men migrated to Alexandria, Virginia to build and later work at Potomac Yard. The arrival of large numbers of Italians created racial tension with both native-born whites and African Americans.

Background Reasons for Italian Emigration 1880-1920.

There were many reasons Italian immigrants left Italy to come to the United States between the years 1880 and 1920. One major factor was the Revolutions of 1848, which lasted until 1871 in Italy. These Revolutions resulted in Italian Unification or the Risorgimento, which in Italian means ‘Rising Again.’ The Risorgimento faciliated Italian migration, argues historians Luciano J. Iorizzo and Salvatore Mondello and the authors of The Italian Americans, stating that the unification of Italy “sparked the exodus which led almost nine million Italians to cross the Atlantic to North and South America in search of socioeconomic promises denied them by the movement which they had supported.”[i] The region most negatively affected by Italian Unification in 1871 was southern Italy and its peasant farmers. Most governmental aid for industrialization was given to northern Italy, leaving the South with continued problems of poverty and high unemployment. Other push factors that led many Italians to leave, including malnutrition, starvation, government oppression, and abusive landowners. Many Italians immigrated to the United States for economic opportunities. Wages were extremely low in Italy for skilled and unskilled laborers, especially compared to wages in the United States.[ii]

Labor in Alexandria

Potomac Yard, ca. 1920. Creator(s): Theodor Horydczak, photographer

Repository: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division,

http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/thc1995006803/PP/

In 1906, Potomac Yard opened in Alexandria, becoming a major employer of Italian immigrants within the region. The process of building Potomac Yard began in the 1850s. By the 1880s, Italians arrived in Alexandria in search of work. Most of these unskilled laborers were young single men, without families. The relationship between African Americans and Italians was often tense because they worked closely together and competed for jobs. Furthermore, native-born whites often saw Italians and African Americans as socially equal because they both were unskilled laborers. Alexandria was much like other southern cities in this way. Native-born white Louisianans stigmatized Italians for laboring alongside African Americans too.

In both areas, Italians were able to escape this association by moving into other lines of work and socially separating themselves from African Americans. Another smaller group of Italians living in Alexandria were small business owners. These men and women were fruit sellers, shoemakers, and carpenters. “It was no accident that when Italians turned to agriculture in the New World they specialized in fresh fruits, tomatoes, and vegetables, the products that had not failed them in the old country” said Iorizzo and Mondello in their book, The Italian Americans.[iii] Unlike the unskilled laborers at Potomac Yard, these Italians were usually family units who settled in Alexandria for a long period of time.

Margaret Ripley Wolfe describes Italian immigrants’ labor experiences in Wise County Virginia, in her article “Aliens in Southern Appalachia, 1900-1920: The Italian Experience in Wise County, Virginia,” noting that without substantial numbers to forms unions, Italians were also subjected to harsh working conditions and high mortality rates.[iv] These circumstances in Wise County mimic conditions in Alexandria, Virginia, where many Italian laborers held very dangerous jobs as documented in newspaper articles from the Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and Evening Star.

An example of dangerous working environments for young, Italian laborers in Alexandria was reported on December 18, 1903 in the Evening Star. Twenty-two year old Lorenzo Basque was struck and killed by one of the work engines at the rail yards.[v] The Evening Star also reported that Basque was escorted by twelve fellow Italian laborers to the Alexandria Hospital “who were employed with him in the construction of the double track of the Richmond, Fredericksburg and Potomac Railroad, about fifteen miles below the city.”[vi] Despite the well-documented hazardous working conditions on the railroad, many Italians migrated to the area looking for railroad work. Perhaps the potential monetary benefits outweighed the risk; it also could be that there were few job opportunities for Italians. Railroad construction and maintenance required large amounts of labor that many Italians took advantage of.

Social Status

Middle and upper class Protestant whites viewed Italians as socially equal to African Americans because they worked in the same industries, primarily the railroad industry at Potomac Yard. Italians viewed themselves as “white” in an effort to raise their social status above African Americans and to escape the racial stigma attached to blackness in the Jim Crow South. Below are two social ladders demonstrating how whites and Italians viewed social status in Alexandria, Virginia.

This Social Ladder shows how upper and middle class Protestant whites viewed social status in Alexandria.

Violence in the News

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Italian immigrants are frequently represented in the newspapers such as The Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and the Evening Star as perpetrators of crimes or victims of crimes. The coverage surrounding Italians played on nativist fears about local whites.

Reports often covered disputes between Italians and other racial groups. Racialized language was often used to describe Italians and African Americans. Furthermore, some reports on Italians confused them with African Americans. This is significant because it points to the belief among native-born whites that Italians and African Americans were interchangeable. A Washington Post article covering the shooting of a police officer in 1907 mistook an Italian named Leanto for an African American. The headline read, “Deputy Sheriff Desperately Wounded by a Resisting Negro.”[vii] Later reports on the capture and trial of Leanto correct this mistake and identify him as an Italian. Another example of this can be found in an article from the Washington Post in May of 1892, when a man named Robinson was arrested for assaulting two older women. The Post reported that, “[Robinson] is not Italian, as some pronounced him to be, but a mulatto.”[viii] The fact that Robinson was presumed to be Italian points to the fears that native whites had of Italian men supposedly molesting white women. This was doubly true in the South as the fear of racial mixing, which arose during this time, was combined with southern fears of black men raping white women. As Italians were so closely associated with African Americans, these accusations fell on them as well. These fears often lead to lynchings. A June 4, 1885 newspaper article describes “Pietro Leone, an Italian . . . charged with attempting to commit outrage upon a little girl aged eleven years.”[ix] The girl in question, the paper reports “stoutly denied” that Leone had committed any assault on her, but other people present had seen him do so. In this situation, it is hard to reconcile conflicting descriptions of the scene. The crowd may have seen an innocent act by Leone and interpreted it as dangerous or the young girl may have covered up the incident to escape the stigma of being a victim of sexual crime. Another instance of sexual assault was reported on November 9, 1920 by the Washington Post. This article described Joseph Caersar, an Italian fruit seller, who was arrested for the alleged assault of a girl. Caersar was “waived a preliminary investigation and was immediately sent out of the city to avoid any attempt at mob violence.”

An interesting thing about these reports, though decades apart, both men in question were fruit sellers. Whether these reports were true or not, and even though a fruit seller was a popular job among Italian immigrants, it is interesting that these are the two instances of “molestation.” It is possible that these men were seen as suspect by the white community because they were not employed alongside African Americans. They were Italians, gaining respectable footing in Alexandria’s commercial corridor, and were brought down again by these charges.

Whites feared Italian immigrants during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries because of their supposed foreignness and racial ‘in-betweenness.’ Newspapers, including the Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and Evening Star, played on these fears by portraying Italians as morally suspect and near the bottom of a racialized social hierarchy. To do this, newspapers mostly reported stories on Italians committing crimes or being the victims of violence. According to Andrew Rolle’s dissertation, “The Immigrant Upraised: Italian Adventurers and Colonists in an Expanding America,” Italians were often associated with crimes in newspapers. “Discrimination was frequently entwined with accusations of criminality. The racial tension of the day turned public attention on weaknesses of foreign minorities, damaging their reputations and making them all subject to suspicions.”[x] Many crime reports focused on incidents between Italian immigrants and African Americans, which play to racist and nativist politics of the time. Rolle also argues that nativism affected Italians’ acculturation. “Nativism, mixed with the undeniable criminality of some immigrants, seriously damaged their acculturative process.”[xi] In response, Italians tried to claim white privilege so that they could be protected from Jim Crow segregation.

An Alexandria Gazette article from April 23, 1904 mentioned mob violence perpetrated by a small group of black men who reportedly came into Alexandria from their work camps along the Potomac River. In this article, the citizens were warned of further disruptions and robberies being likely as “the environs of the city are swarming with Negroes and Italians.”[xii] The language used in this article portrays Italians along with African Americans as susceptible to causing trouble. The article also notes that these men “flock to certain places when they enter the city.”[xiii] It can be inferred that the places meant here are taverns and saloons, as one is mentioned earlier in the article. Portraying Italians as drunken, criminal, and highly explosive was another way of pointing out their differences from native-born white men. Another 1904 article in the Alexandria Gazette pointed to alcohol as the cause of violence between two Italian laborers living at the “Garfield Park Camp.” According to the article, Luigi Palmitano was “arrested for committing a deadly assault upon Rocco Ferrio,” another Italian laborer.[xiv] The article notes that the shooting occurred over a “beer argument over a game of cards.”[xv] This article informed the public that this deadly incident happened due to alcohol and gambling, and would have been a very effective way to highlight how different Italians supposedly were from local whites.

Italians resented the ill treatment and low status that came with being associated as “black” or not white. Some instances in which Italians fought against these perceptions can also be noted in local newspapers. One Washington Post article that records both the resentment that Italians felt towards their low status and against blacks was published on the December 4, 1904.[xvi] This article quotes an Italian named Alfonso, saying “blacka [sic] man taka [sic] white-a [sic] man’s job” after shooting an African American man named James Winkfield outside a saloon.[xvii] Rudolph J. Vecoli, author of the essay, “Italian Americans and Race: To Be or Not To Be White,” comments on the tensions between Italians and African Americans, arguing “[r]elations between Italians and African Americans were not always amicable. Economic competition, rather than race per se, appeared to have provoked hostilities between them.”[xviii] According to a second article on Winkfield’s attack, a “well known colored resident, was accosted by an Italian who drew a pistol and declared “all d****d negroes should be killed.”[xix] These attacks along with the recorded words of Alfonso help to illuminate the tensions that were building among Italians, local whites, and African Americans. Italians, who competed with African Americans for similar jobs, wished to escape the bonds of the Jim Crow South by claiming their “white” status. Their frustrations accumulated and violence sometimes resulted.

Lynching

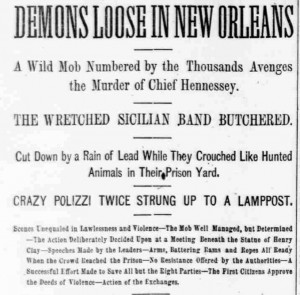

The 1891 lynching of eleven Italians in New Orleans also represents the racial attitude towards Italians in the South. On October 15, 1890, David C. Hennessy, the police chief of New Orleans, was shot and killed outside his home in an effort to keep him from testifying in a case. The New Orleans Times, reported that, after they killed Hennessy, the Italians “were as dumb as clams.”[xx] About a year later after the alleged killers were found not guilty, a white mob showed up at the prison, broke down the door, and publicly lynched eleven of the sixteen Italian men who were being held for Hennesy’s murder. After the mob lynched the eleven Italians, the New Orleans Times responded with praise, stating that “desperate diseases require desperate measures.”[xxi] The newspapers coverage of the entire ordeal often used racist language towards the Italians, calling them “dagos” and “demons.”

Similar language can be found in newspaper articles from the Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and the Evening Star with the 1905 murder of police officer and school teacher George Malcolm at the hands of Italian immigrant Joseph Leanto in Lorton, Virginia. Leanto, a railroad worker, had reportedly “made undue remarks regarding young lady scholars,” and Malcolm was sent to arrest him when a shoot out occurred. The first reports on the incident were published on April 7, 1905 in the Washington Post and Alexandria Gazette. The Washington Post claimed that the part-time police officer, part-time teacher was killed by a “negro,”[xxii] while the Alexandria Gazette correctly identified Leanto as Italian. After Malcolm was taken to the hospital (where he later died), Leanto ran away, and was later found by a large group of white men identified in the Alexandria Gazette as J. M. Springman, John Plaskett Jr., Lindsey Dawson, Peter Hall, Elmer Mallory, George Bayliss, A. W. Grimsley, and R. L. Harrover who claimed Leanto committed suicide.[xxiii] There was a great deal of racially driven language used throughout the newspaper coverage in which they called Leanto names, such as “assassin” and an “enraged fiend.” The confusion surrounding the suicide led the Italian Ambassador, Baron Mayor des Planches, to call for a federal and state investigation. He believed that Leanto was actually lynched by a white mob seeking retaliation for the death of Malcolm. After an investigation, the State Department concluded that there was no foul play and that Leanto committed suicide. It is still very possible, however, that this was a cover up for white mob violence. Late that year, the Evening Star reported that “Joseph Leanto, an Italian, resisted arrest in Virginia and killed Deputy Sheriff Malcolm. He was shot by a posse of citizens and died at the Emergency Hospital in this city. His victim died in the same hospital.” [xxiv]

Similar language can be found in newspaper articles from the Washington Post, Alexandria Gazette, and the Evening Star with the 1905 murder of police officer and school teacher George Malcolm at the hands of Italian immigrant Joseph Leanto in Lorton, Virginia. Leanto, a railroad worker, had reportedly “made undue remarks regarding young lady scholars,” and Malcolm was sent to arrest him when a shoot out occurred. The first reports on the incident were published on April 7, 1905 in the Washington Post and Alexandria Gazette. The Washington Post claimed that the part-time police officer, part-time teacher was killed by a “negro,”[xxii] while the Alexandria Gazette correctly identified Leanto as Italian. After Malcolm was taken to the hospital (where he later died), Leanto ran away, and was later found by a large group of white men identified in the Alexandria Gazette as J. M. Springman, John Plaskett Jr., Lindsey Dawson, Peter Hall, Elmer Mallory, George Bayliss, A. W. Grimsley, and R. L. Harrover who claimed Leanto committed suicide.[xxiii] There was a great deal of racially driven language used throughout the newspaper coverage in which they called Leanto names, such as “assassin” and an “enraged fiend.” The confusion surrounding the suicide led the Italian Ambassador, Baron Mayor des Planches, to call for a federal and state investigation. He believed that Leanto was actually lynched by a white mob seeking retaliation for the death of Malcolm. After an investigation, the State Department concluded that there was no foul play and that Leanto committed suicide. It is still very possible, however, that this was a cover up for white mob violence. Late that year, the Evening Star reported that “Joseph Leanto, an Italian, resisted arrest in Virginia and killed Deputy Sheriff Malcolm. He was shot by a posse of citizens and died at the Emergency Hospital in this city. His victim died in the same hospital.” [xxiv]

Conclusion

Due to nativist ideologies, Alexandria, Virginia resembled a typical Jim Crow southern city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many young Italian men migrated to Alexandria to work in Potomac Yards but most did not ultimately settle there. Some Italian family units that did settle there were skilled laborers and small business owners. These families can be seen in Alexandria’s U.S. Census Data and in a few newspaper articles from the immediate area. Racial tensions between the Italians and other immigrant groups can be attributed to their labor relations with African Americans and their general “foreignness” that evoked fear in the native born white population. Newspapers perpetuated this racial fear by casting Italians as consistently involved in crimes whether they were the aggressors or victims. Despite our own research on Italian immigrants in Alexandria, Virginia more historiography surrounding immigrants in the South needs to be produced. Few outside conclusions can be made about Italian immigrants in Alexandria, Virginia, due to the small amount of primary sources available documenting Italians in the South.

About the Authors

Kayla Toussant, Austin Clay, and Jessica Scatchard are senior history majors at the University of Mary Washington. They have spent the Fall 2014 semester researching Italian Immigration in the U.S. South and more specifically in Alexandria, Virginia. Their findings are based off of primary and secondary sources.

[1] Luciano J. Iorizzo and Salvatore Mondello, The Italian Americans (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1980), 19.

[2] Iorizzo and Mondello, The Italian Americans, 60.

[3] Ibid, 57.

[4] Margaret Ripley Wolfe, “Aliens in Southern Appalachia, 1900-1920: The Italian Experience in Wise County, Virginia,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 87, no, 4 (Oct,, 1979): pg. 455-472. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4248343

[5] “Death From Injuries,” The Evening Star, December 18, 1903.

[6] Ibid.

[7]“Deputy Sheriff Desperately Wounded by a Resisting Negro,” The Washington Post, April 7, 1905.

[8] “ALEXANDRIA AFFAIRS: Better Streets Wanted–Will Protect His Prisoner,” The Washington Post, May 2, 1892.

[9] “Alexandria,” Washington Post, June 4, 1885.

[10] Andrew F. Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised: Italian Adventurers and Colonists in an Expanding America (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press: 1968), 102.

[11] Rolle, The Immigrant Upraised, 108.

[12] Alexandria Gazette, April 23, 1904.

[13] Ibid.

[14] “Charged with Assault.” Alexandria Gazette, November 25, 1904.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Italian Fires Two Bullets into Negro, Seriously Wounding Him,” The Washington Post, December 4, 1904.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Rudolph J. Vecoli, “Italian Americans and Race: To Be or Not To Be White,” in ‘Merica: A Conference on the Culture and Literature on Italians in North America ed. By Aldo Bove and Giuseppe Massara (Stony Brook: NY: 2006), 99.

[19] “War on Negroes,” The Alexandria Gazette, December 5, 1904.

[20] The New Orleans Times-Democrat, October 16, 1890.

[21] The New Orleans Times- Democrat, March 15, 1891.

[22] “Deputy Sheriff Desperately Wounded by Resisting a Negro,” The Washington Post, April 7, 1905.

[23] “Dual Tragedy at Lorton,” Alexandria Gazette, April 10, 1905.

[24] “Crimes and Criminals: Unusual Number of Cases of Murder and Suicide,” Evening Star, January 1, 1906. Special thanks to Erin House for discovering this article.

One thought on “Italian Immigrants in Alexandria, VA, Part I”